In the 1990’s, the concept of a functioning virtual reality (VR) system was still in many ways a science fiction fantasy — but that is no longer the case. Multiple developers, most notably Google and Oculus Rift (acquired last year by Facebook), have made VR into a real thing that could be as common as smartphones over the next decade — and VR could prove a valuable new tool for the music industry.

VR companies have developed an immersive media format that lets users dive into audiovisual content by wearing a headset, also known as Head Mounted Display or HMD, allowing the user to feel as if he or she is part of the content, and in certain situations even allowing users to interact with their virtual environment.

When wearing a HMD, the user can experience content in 360 degrees by simply looking around. The HMD tracks movement and generates images and content to match. The most common experience available to the public at this point is passive content, where you experience images and videos without interacting them — but that won’t be the case for long, and even without interacting with your environment VR is extremely immersive.

The gaming industry has been at the forefront of this field, testing beta projects that experiment with immersive multiplayer games, as well as first-person games that allow users to virtually put themselves in the shoes of the character they are using.

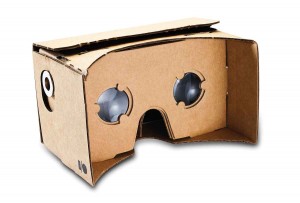

Google Cardboard and the Samsung Gear VR are the some of the first HMDs made widely available to the average consumer. In the world of journalism, The New York Times recently partnered with Google for a VR project. The Times shipped 1 million Google Cardboard headsets to their sunday-print subscribers on November 7th. Subscribers were able to use Google Cardboard with the NYT VR app to access content formatted specifically for VR.

It might look like a publicity stunt, but it’s much more than that. VR content has an extremely high capacity for depth and detail, and could prove vital to a new generation of newsmakers. Moreover, VR potentially allows the audience to experience the situation of the people portrayed in the news by taking a walk down a war-torn street in Syria or having a conversation with a refugee. VR allows for previously unrivaled user engagement.

But where does music fit into all of this virtual reality talk?

There have been some interesting VR projects related specifically to music. In August 2014, Paul McCartney recorded a live concert with 360-degree cameras located in strategic spots that allowed people with HMDs to experience the concert as if they were standing on stage.

Taylor Swift, Jose Gonzalez and Beck have also experimented with VR music videos or live shows. With the help of director Chris Milk, Beck recorded a live performance of his song, “Hello Again,” with 360-degree cameras, as well as a spherical binaural audio device to create a fully immersive surround soundscape

Yet, all these projects are essentially fancy experiments and extended beta testing — the vast majority of consumers still don’t own a VR HMD. However, that will soon change as time passes and VR becomes cheaper and begins to be adopted as mainstream technology. Musicians should not overlook the opportunity that VR presents.

VR has the potential to open a new reality for the music industry. VR will make it possible for musicians to generate rich context to surround their music and engage with their audiences in deeper ways and with many more people at the same time. This will allow them to foster loyal audiences that feel more like a community of friends that a collection of like-minded consumers

Imagine being able to listen to an album while being immersed in a world created specifically to match the feelings of the music. Imagine going to to an intimate concert featuring your favorite band and having the ability to interact, not only with the audience around you, but also with the artist in performance. Now imagine that you did all of this without leaving your couch. This type of VR engagement could lead to stronger brand awareness for the artist and potentially an alternate revenue stream, bringing artists closer to their audiences — no matter where they are.

by Alonso Villagomez